Autonomic dysreflexia

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) is a medical emergency that occurs in people with a spinal cord injury (SCI) at or above the T6 level. It is characterised by a sudden rise in systolic blood pressure (BP) – typically more than 20 mmHg above the individual’s usual resting baseline. It occurs in response to a triggering stimulus, most often something irritating or painful (noxious) below the level of injury, such as a full bladder or bowel. Because communication between the body and brain is disrupted, this leads to uncontrolled activation of the sympathetic nervous system leading to a sudden rise in BP. Symptoms range in severity and may include a pounding headache, sweating, blotchy rash, chest tightness, blurred vision, nasal congestion, piloerection and anxiety. Untreated episodes can result in stroke, seizures, myocardial infarction and death.

Increase in blood pressure 20-40 mmHg above person’s usual BP.

- note: “Usual BP” is often lower than the general population for people with a high level spinal cord injury, e.g. around 90/60

Pounding headache

Bradycardia (slower than normal heart rate)

Sweating above the level of the injury

Flushed or blotchy skin above the level of injury

Chest tightness, difficulty breathing

Anxiety or feeling of unease

Piloerection (goosebumps)

Nasal congestion

Not all people experience signs of autonomic dysreflexia (AD). This is called ‘silent’ AD or asymptomatic AD. Asymptomatic AD should be assessed and managed with the same clinical urgency as in cases where symptoms are present.

Autonomic dysreflexia is a medical emergency. Call 000 if required.

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) is often triggered by irritating or painful (noxious) stimuli below the level of spinal cord injury, even if the person cannot feel the stimulus. The following are common causes:

Bladder

- overfull bladder – often due to a blocked or kinked catheter, or missed intermittent catheterisation

- urinary tract infection (UTI)

- bladder or kidney stones – calculi can irritate the urinary tract

Bowel

- constipation or faecal impaction

- rectal trauma or conditions such as haemorrhoids, anal fissures, or rectal prolapse

Procedures

- instrumentation procedures like colonoscopy, cystoscopy

Skin

- pressure injuries or skin damage e.g. burns

- tight or restrictive clothing or equipment – Such as abdominal binders, compression stockings, or tight shoes

- ingrown toenails

Musculoskeletal causes

- fractures, noting that:

- these may go unnoticed due to lack of sensation.

- people with SCI are at higher risk of fractures due to low bone density (osteoporosis), especially in the distal femur and proximal tibia

Reproductive and abdominal causes

- abdominal emergencies – such as appendicitis, cholecystitis (inflammation of the gallbladder), or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

- menstruation

- pregnancy and labour

- testicular conditions – such as testicular torsion and epididymo-orchitis (inflammation of the epididymis and testicle)

- sexual activity and orgasm

Other causative factors of hypertension should be considered if:

- there is a pre-existing diagnosis of hypertension

- a specific cause cannot be identified at the time of the hypertensive episode

- the blood pressure doesn’t reduce after the potential cause has been resolved

Understanding autonomic dysreflexia

A spinal cord injury at or above the level of T6 causes dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system. This includes the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). As a result, communication between the body and brain is disrupted. Sympathetic and parasympathetic (autonomic) nerve signals cannot effectively pass across the damage to the spinal cord. This impairs the body’s ability to respond to a trigger (e.g. noxious stimulus) occurring below the level of spinal injury.

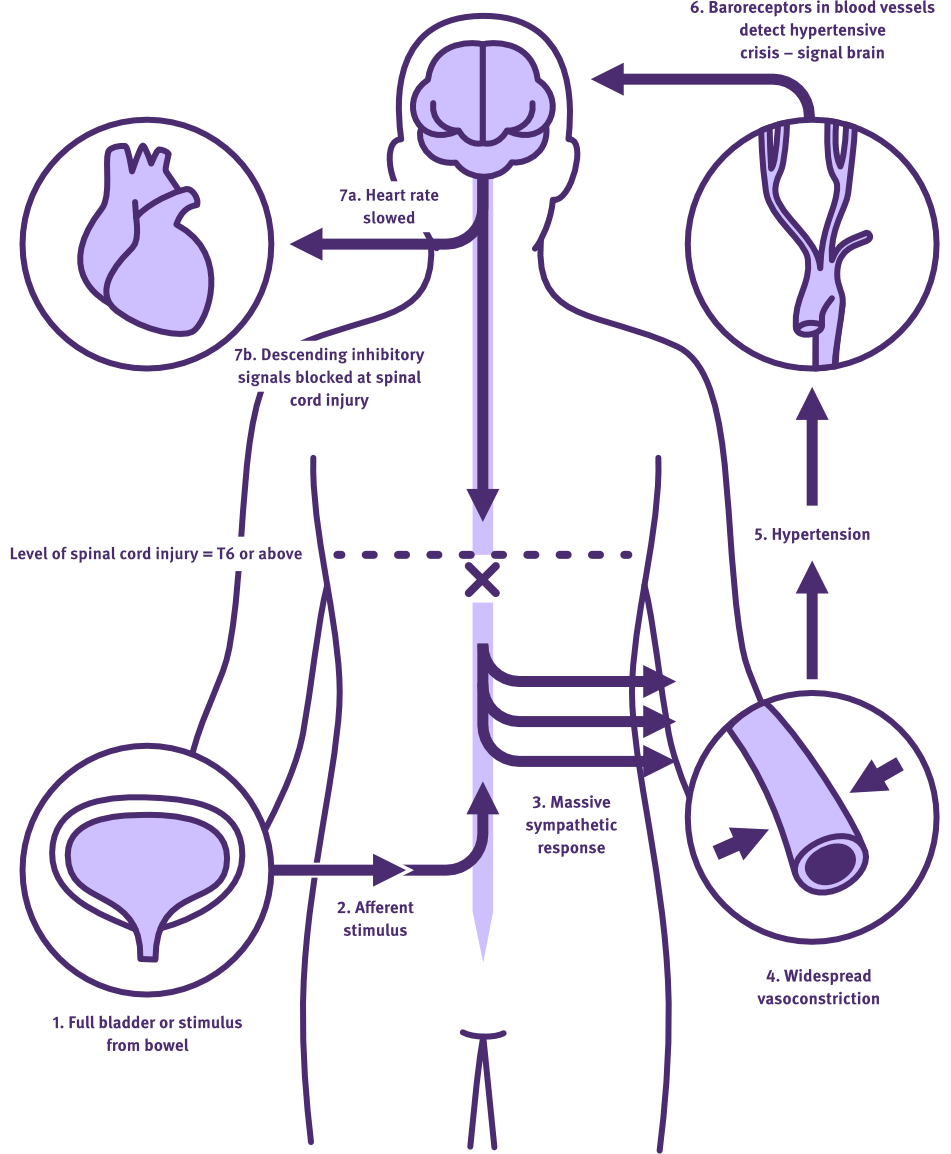

Chain of events

Below is a step-by-step overview of the pathophysiology of autonomic dysreflexia:

1. Noxious stimulus below the level of injury

A noxious (irritating or painful) stimulus occurs below the spinal injury (e.g. full bladder, constipation, skin irritation).

→ this sends afferent signals (sensory messages) up the spinal cord, however they cannot transmit past the injury level.

2. Sympathetic response

The stimulus activates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) below the level of injury.

→ this leads to widespread vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels), causing a rapid rise in blood pressure (hypertension).

3. Brain detects hypertension

Baroreceptors (pressure sensors) in the carotid sinus and aortic arch detect the hypertensive crisis (elevated blood pressure).

→ they signal the brain to activate the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) via the vagus nerve in an attempt to slow the heart and reduce blood pressure.

4. Parasympathetic response is incomplete

The parasympathetic signals can travel down the spinal cord only as far as the level of injury, not below.

→ this causes:

- bradycardia (slowed heart rate)

- vasodilation above the injury (flushed skin, sweating)

The sympathetic overactivity continues unchecked below the injury level.

5. Ongoing crisis until the trigger is resolved

The hypertensive crisis will persist until the noxious stimulus is identified and removed.

Without intervention, autonomic dysreflexia can result in stroke, seizure, cardiac arrest, or death.

Without intervention, autonomic dysreflexia can result in stroke, seizure, cardiac arrest, or death.

Diagram illustrating how autonomic dysreflexia occurs in a person with spinal cord injury

Adapted from: Blackmer (2003)

Call 000 in an emergency. The following education video from the UK references a non-Australian emergency number.

Management

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) is a medical emergency that requires prompt recognition and action. Follow these steps to manage an AD episode safely and effectively.

Immediate actions

- If possible, position the person upright (or elevate the head of the bed) to help lower blood pressure.

- Call for assistance – notify nursing and medical staff immediately.

- Check blood pressure (BP) every 2–5 minutes.

- Loosen or remove tight clothing, e.g. abdominal binders, compression stockings, shoes.

Investigate and remove the cause

- Ask the person if they suspect a cause.

- If needed, hoist them back to bed for a full assessment.

Bladder

- Check catheter tubing: if it feels cool, it is likely it isn’t draining. It may be blocked or kinked.

- Inspect urine bag: check the volume of urine in the bag. Assess urine output and compare with fluid intake.

- Perform a bladder scan (if available) to assess for urinary retention.

- If intermittent catheterisation is usually used, consider performing one regardless of timing.

- If the bladder is overfull, drain 500 mL initially, then 250 mL every 10–15 minutes to avoid rebound hypotension.

Bowel

- Obtain a history of the recent bowel output.

- Perform a digital rectal examination using lignocaine gel.

- Ensure systolic blood pressure is below 150 mmHg before starting the rectal exam.

- Check BP every 2 minutes during the exam.

Skin

- Conduct a full skin check: look for pressure injuries, wounds, burns, infections, or ingrown toenails.

Other potential causes

If the cause remains unclear, work with the medical team to assess for other common triggers:

- fractures

- renal or bladder stones

- menstrual cycle, pregnancy, or labour

- other abdominal or systemic issues (e.g. appendicitis, epididymo-orchitis).

Pharmacological management

If systolic BP is above 170 mmHg, pharmacological intervention should be considered:

First-line: Glyceryl Trinitrate

- Glyceryl trinitrate should be used if the cause cannot be alleviated quickly or is difficult to isolate.

- Check for contraindications: do not use glyceryl trinitrate if the person has taken:

- Sildenafil (Viagra) or Vardenafil (Levitra) in the last 24 hours

- Tadalafil (Cialis) in the last 4 days

→ as this can cause significant hypotension once an episode of AD has resolved.

Dosage options:

- 1 spray (400 microg) GTN (nitrolingual pump spray) under the tongue

- OR apply a 5 mg transdermal GTN patch to chest/upper arm.

→ Remove the patch once BP stabilises (usually SBP less than 130 mmHg; individual thresholds may vary).

- Monitor BP every 2–5 minutes after medication is administered.

- Repeat sublingual GTN every 5–10 minutes if needed, under medical supervision.

If Glyceryl Trinitrate is unavailable or contraindicated

- Administer Captopril 25 mg sublingually

If glyceryl trinitrate or captopril do not lower the blood pressure sufficiently and the cause of AD has not been identified, please contact the Queensland Spinal Cord Injuries Service:

- Phone Princess Alexandra Hospital Switch: Ph (07) 3176 2111 and ask for the Spinal Injuries Unit Registrar (business days) or on-call Spinal Injuries Unit Consultant (after-hours)

- arrange transport to the nearest emergency department. Call 000 if required.

Ongoing monitoring

- Continue to monitor vital signs for at least 4 hours after the episode.

- Watch for rebound hypotension or other delayed symptoms.

Documentation

Document the following in the medical record:

- identified cause of autonomic dysreflexia

- signs and symptoms experienced

- all interventions performed

- BP trends and response to intervention

- medication administered and response

- Plan for follow-up (e.g., urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity test (MCS), medication changes, bowel regimen changes, investigations)

Resolution criteria

Autonomic dysreflexia is considered resolved when:

- blood pressure and heart rate return to baseline

- no ongoing symptoms (e.g. headache, flushing, anxiety)

Follow-up care and education

After an episode of autonomic dysreflexia, the person may experience residual effects from catecholamine release. Catecholamines are stress-response hormones that are released in excess during autonomic dysreflexia due to uncontrolled activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

It is important to monitor for lingering symptoms, which may include:

- anxiety

- disturbed sleep

- restlessness or fatigue

Provide reassurance and support, and consider further follow-up if symptoms persist or interfere with recovery.

Education

- Educate the person and, if relevant, their family/support workers on:

- common triggers (bladder, bowel, skin)

- early warning signs

- use and storage of any prescribed emergency medications (e.g., GTN spray or patch)

- Ensure appropriate discharge planning, including access to medications and follow-up supports.

Prevention

Prevention is the best management strategy. Support the person to maintain:

- regular bladder and bowel routines

- good skin care and pressure relief practices

- awareness of early AD symptoms and when to seek help

Management of Autonomic Dysreflexia

Queensland Spinal Cord Injuries Service, Queensland Health

Treatment of autonomic dysreflexia for adults and adolescents with spinal cord injuries

State of New South Wales Agency for Clinical Innovation (NSW ACI)

Treatment of autonomic dysreflexia for adults and adolescents with spinal cord injuries: A guide for clinicians in non-specialist units

State of New South Wales Agency for Clinical Innovation (NSW ACI)

Treatment Algorithm for Autonomic Dysreflexia

State of New South Wales Agency for Clinical Innovation (NSW ACI)

Autonomic dysreflexia

SCIRE Professional

Autonomic Dysreflexia – New Zealand Spinal Trust

New Zealand Spinal Trust

Agency for Clinical Innovation. (2025, March). Treatment of autonomic dysreflexia for adults and adolescents with spinal cord injuries: A guide for clinicians in non-specialist units. https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/155149/ACI-Treatment-of-autonomic-dysreflexia-for-adults-and-adolescents-with-spinal-cord-injuries.pdf

Blackmer, J. (2003). Rehabilitation medicine: 1. Autonomic dysreflexia. CMAJ, 169(9), 931–935. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC219629/

Krassioukov, A., Blackmer, J., Teasell, R. W., & Eng, J. J. (2018). Autonomic dysreflexia and other autonomic dysfunctions following spinal cord injury. In J. J. Eng, R. W. Teasell, W. C. Miller, D. L. Wolfe, A. F. Townson, J. T. C. Hsieh, V. K. Noonan, E. Loh, S. Sproule, A. McIntyre, & M. Querée (Eds.), Spinal cord injury rehabilitation evidence (Version 7.0, pp. 1–50). SCIRE Project. https://scireproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/AD-Chapter-2018-FINAL-compressed.pdf