Pain management

Acute pain management

Acute pain is typically of sudden onset and can be severe in intensity. It is generally managed using standard medications and supportive treatments such as heat or cold therapy, massage, and physiotherapy. Acute pain usually improves over several weeks as the damaged tissues heal.

Persistent pain management

Persistent (chronic) pain is often more complex and difficult to treat. While clinicians are often driven by a strong desire to help, this can sometimes result in the over-prescription of medications. This is particularly concerning for people with spinal cord injury (SCI), who may be more physiologically vulnerable and at increased risk of adverse effects, such as respiratory depression or gastrointestinal complications.

Effective management of persistent pain requires a multidisciplinary approach with an emphasis on psychosocial factors. The ultimate goal is to support individuals in developing self-management strategies that help maintain function and quality of life despite ongoing pain.

Pain assessment

Pain assessment should be holistic, considering the following key factors:

- Types of pain: people may experience a combination of acute, persistent, neuropathic, nociceptive and nociplastic pain.

- Multifactorial influences: pain is shaped by interrelated and modifiable factors, including:

- immune and inflammatory responses, which may be influenced by comorbid health conditions

- psychological factors, such as grief, loss, depression, or anxiety, particularly following SCI

- behavioural responses, including avoidance behaviours and pain-related activity patterns

- physical health changes, including altered activity levels and deconditioning

- social factors, such as reduced social engagement or changes in identity

- environmental influences, including housing quality and accessibility.

Integrating these elements into a comprehensive pain management plan ensures a more accurate understanding of the person’s experience and supports more effective, individualised interventions.

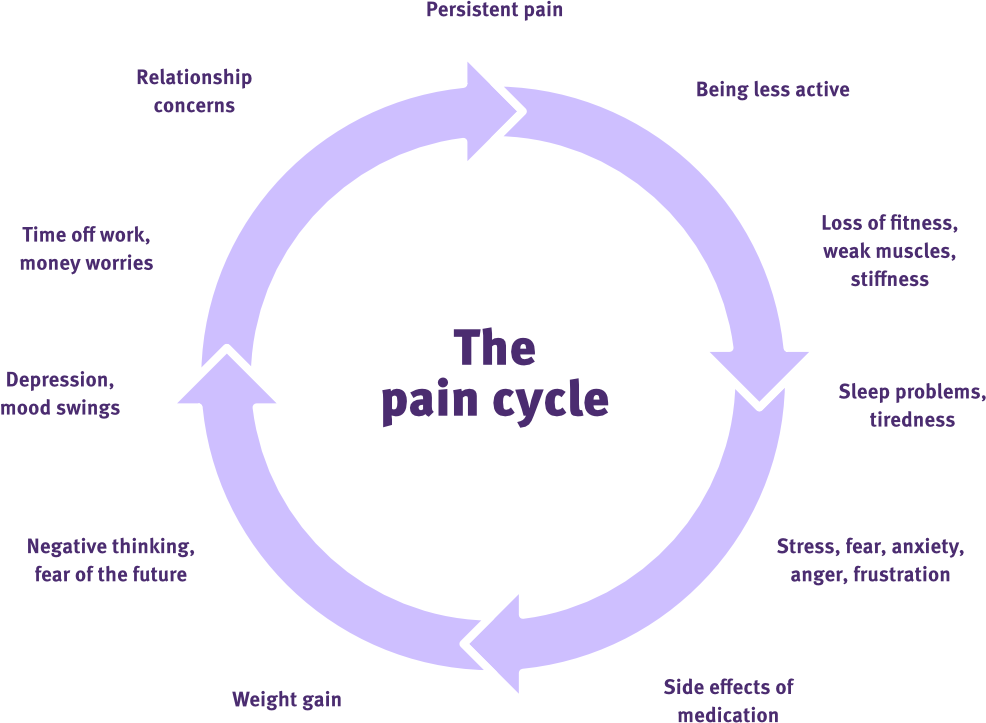

Pain cycle explained

The pain cycle

Adapted from Live Well with pain

Different thoughts, behaviours, emotions, foods and social interactions can affect the experience of pain. These are all points for therapeutic modification of the pain cycle.

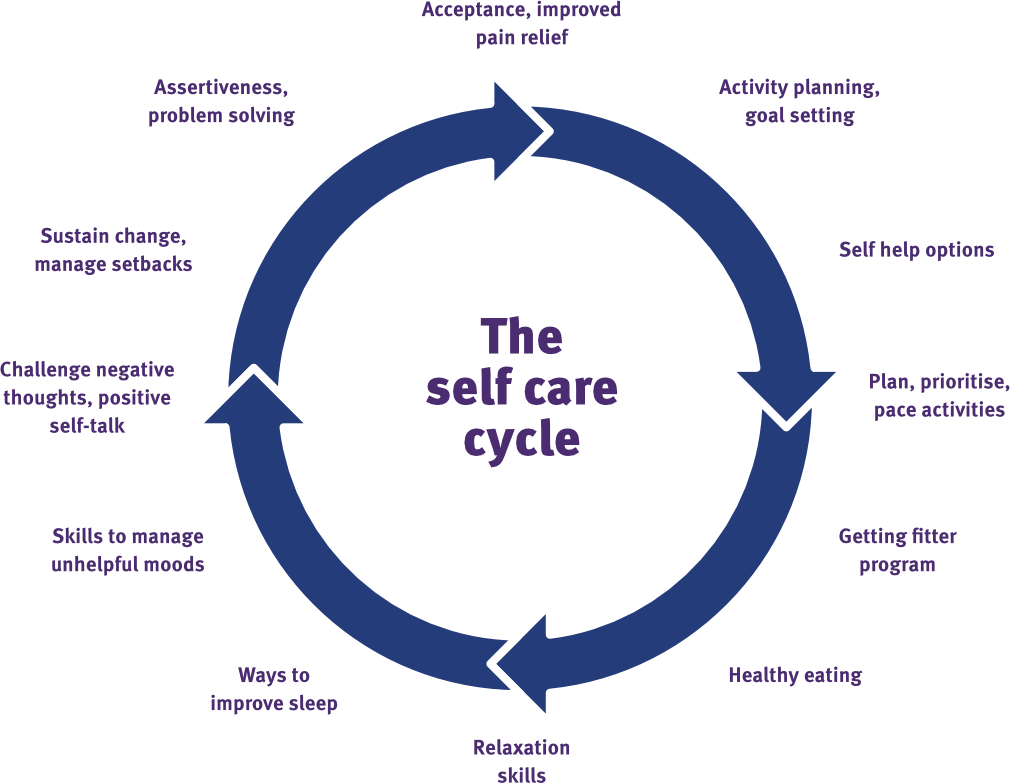

The self care cycle

Adapted from Live Well with pain

Developing a management plan for persistent pain

Persistent pain is often sustained by a cycle of perceived threat or danger, influenced by multiple modifiable factors. These factors can either intensify or help relieve pain, and should be addressed as part of a personalised pain management plan:

- Immune and inflammatory responses: manage comorbid conditions and promote general health through appropriate medical care and access to resources

- Psychological wellbeing: support mental health by addressing grief, trauma, anxiety, depression and substance use concerns

- Behavioural patterns: identify and reframe avoidant behaviours and relationship withdrawal

- Physical guarding: encourage gradual re-engagement with daily activities to reduce protective movement patterns

- Social disconnection: reduce isolation and support the rebuilding of identity, purpose and self-esteem

- Environmental conditions: improve housing quality, accessibility and access to essential supports and services.

The overarching goals of pain management

The core aims of pain management are to:

- increase personal agency

- increase perceived safety

- reduce perceived danger

- facilitate engagement with valued activities.

These goals support a shift from threat-based responses to adaptive coping strategies.

Pain acceptance

Pain is often a signal that something in the body needs attention. However, when the underlying cause is stable and no longer poses a threat, individuals can learn to acknowledge and accept the ongoing presence of pain without allowing it to dominate their lives.

Acceptance does not mean giving up. Rather, it involves recognising pain as one part of the overall experience and choosing to live a meaningful and fulfilling life despite it.

Interventions for managing persistent pain

Conversations about pain should be simple, supportive and goal-oriented. They can help build trust, clarify the person’s experience, and support self-management. Useful prompts to guide discussion include:

- “What does your daily routine look like on a good day versus a bad day?”

- “What makes a day feel good or bad for you?”

- “What activities do you avoid when in pain, and which ones do you push through?”

- “What do you feel you’re missing out on because of the pain?”

These questions help uncover patterns, beliefs and behaviours that may influence the pain experience and inform tailored interventions.

Strategies for managing persistent pain

Resilience and adaptation are central to managing persistent pain. The following strategies can support personal growth and improve overall wellbeing:

- Pacing: Break activities into smaller steps with rest breaks. Use short, regular exercise or movement sessions.

- Prioritising: Focus on meaningful and enjoyable activities to guide planning and engagement.

- Avoiding boom-and-bust cycles: Encourage consistent activity levels and proactive planning for more difficult days.

- Education: Reinforce the message that persistent pain, particularly post-SCI, does not always indicate harm.

- Social engagement: Facilitate opportunities for connection, friendship, and community involvement.

Health maintenance considerations

A proactive approach to health maintenance supports the management of persistent pain and promotes overall wellbeing. Key areas include:

• Bowel management: Prevent constipation through regular routines, diet, hydration and appropriate medications.

• Bladder care: Reduce the risk of urinary tract infections and kidney stones through effective catheterisation and hydration strategies.

• Sleep hygiene: Identify and manage sleep disorders, and promote consistent routines and a restful sleep environment.

• Psychosocial support: Address mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, grief or trauma.

• Nutrition: Optimise diet to meet both acute and long-term SCI-related needs, including energy balance and gut health.

• Inflammation management: Support medical and lifestyle strategies that reduce systemic inflammation.

• Sexuality and intimacy: Encourage open discussion and provide access to relevant resources and professional support.

• Substance use: Offer education and support to ensure safe use or to assist with reduction or cessation if needed.

These strategies contribute to a holistic and sustainable approach to managing persistent pain and enhancing quality of life.

Chronic pain clinician resources

Agency for Clinical Innovation (New South Wales)- Pain Managment Network

Statewide persistent pain management services

Queensland Health

Pain Facts

Pain Revolution

Why things hurt video

Lorimer Moseley – TedxAdelaide

Understanding Persistent Pain

Tasmanian Health Service

Is My Pain System Overprotective?

More Good Days

Flippin’ Pain

Flippin’ Pain

Pain management

SCIRE Professional

Chronic Pain Australia

Chronic Pain Australia

Live Well with Pain

Live Well with Pain

Bryce, T. N., Biering-Sørensen, F., Finnerup, N. B., Cardenas, D. D., Defrin, R., Lundeberg, T., Norrbrink, C., Richards, J. S., Siddall, P., Stripling, T., Treede, R. D., Waxman, S. G., Widerström-Noga, E., Yezierski, R. P., & Dijkers, M. (2012). International spinal cord injury pain classification: Part I. Background and description. March 6–7, 2009. Spinal Cord, 50(6), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.156

Mehta, S., Teasell, R. W., Loh, E., Short, C., Wolfe, D. L., Benton, B., Blackport, D., & Hsieh, J. T. C. (2019). Pain following spinal cord injury. In J. J. Eng, R. W. Teasell, W. C. Miller, D. L. Wolfe, A. F. Townson, J. T. C. Hsieh, S. J. Connolly, V. K. Noonan, E. Loh, & A. McIntyre (Eds.), Spinal cord injury rehabilitation evidence. SCIRE Project. https://scireproject.com/evidence/pain/